Preservation Long Island

Cold Spring Harbor, NY

March 24 – May 3, 2024

Mission: Preservation Long Island's mission is to celebrate and preserve Long Island’s diverse cultural and architectural heritage through advocacy, education and stewardship of historic sites and collections. From special projects and exhibitions to preservation advocacy and on-site education, our wide-ranging programs connect Long Islanders to the region's diverse and distinctive past.

Preservation Long Island was excited to serve as the inaugural site for Voices and Votes: Democracy in America, whose themes strongly resonate with our commitment to making the past relevant to the present. The installation was hosted at The Old Methodist Church (1842), a site once visited by Sojourner Truth. Here and at our other historic sites, we interpret Long Island’s history and foster dialogue around the challenges and triumphs that have attended American democracy since its inception.

At Joseph Lloyd Manor (1767), we share the story of Jupiter Hammon, America’s first published Black poet. While enslaved by the Lloyd family, Hammon authored works that grappled with the same democratic ideals debated by our nation’s Founding Fathers. By voicing his vision for the future, Hammon's writings remain a powerful call for Americans to insist that the nation fulfills its promises of liberty and justice for all.

At the Sherwood-Jayne House (ca. 1730), we ask visitors to consider the Revolutionary War from contrasting perspectives. Property-owner William Jayne remained a Loyalist during the British occupation of Long Island, even as neighbors in his community fled to Connecticut as refugees. The experiences of the Jayne family introduce nuance to the idea of the war’s divided allegiances, suggesting that communal bonds sometimes outweighed the conflict between Patriots and Loyalists.

At the Custom House (ca. 1770), we explore the role that local communities play in shaping national policies. The Custom House served as both the civic office and private residence of Henry Packer Dering, Custom Master for the federal port of Sag Harbor following the ratification of the Constitution. The commerce regulated by the Custom House transformed Sag Harbor into a sophisticated cosmopolitan port, helped stabilize the economy of the fledgling United States, and allowed local residents to see themselves not just as New Yorkers, but as citizens of the United States.

Stories from the Community

Long Islanders across history have helped shape the nation, finding ways to make their voices heard and participate in America's democracy - from writings of enslaved author Jupiter Hammon and the Revolutionary-era politics of William Floyd to the more recent activism of the Shinnecock people to protect their sacred burial sites. Drawing on the collections of Preservation Long Island and other local lenders, "Democracy on Long Island" connects the national themes of the Voices and Votes exhibition with Long Island people, stories, and events.

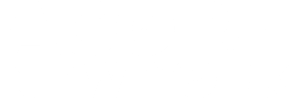

Notice

March 31, 1842

Cold Spring Harbor, New York

Paper, ink

Preservation Long Island, 1999.1

On March 31, 1842, the committee charged with the construction of Preservation Long Island's Headquarters—Cold Spring Harbor’s former Methodist Episcopal Church—issued a notice seeking funds for its completion. On Independence Day the following year, Sojourner Truth (ca. 1797–1883) arrived in Cold Spring Harbor and visited the newly completed church. Born into slavery in Ulster County, she later gained her freedom and became an itinerant preacher and outspoken advocate for abolition, civil liberties, and women’s rights. Truth never learned to read and write, but dictated her autobiography, The Narrative of Sojourner Truth, which brought her national recognition. Its pages describe Truth’s visit to Cold Spring Harbor where she helped with preparations for a mass temperance meeting which began at this very building.

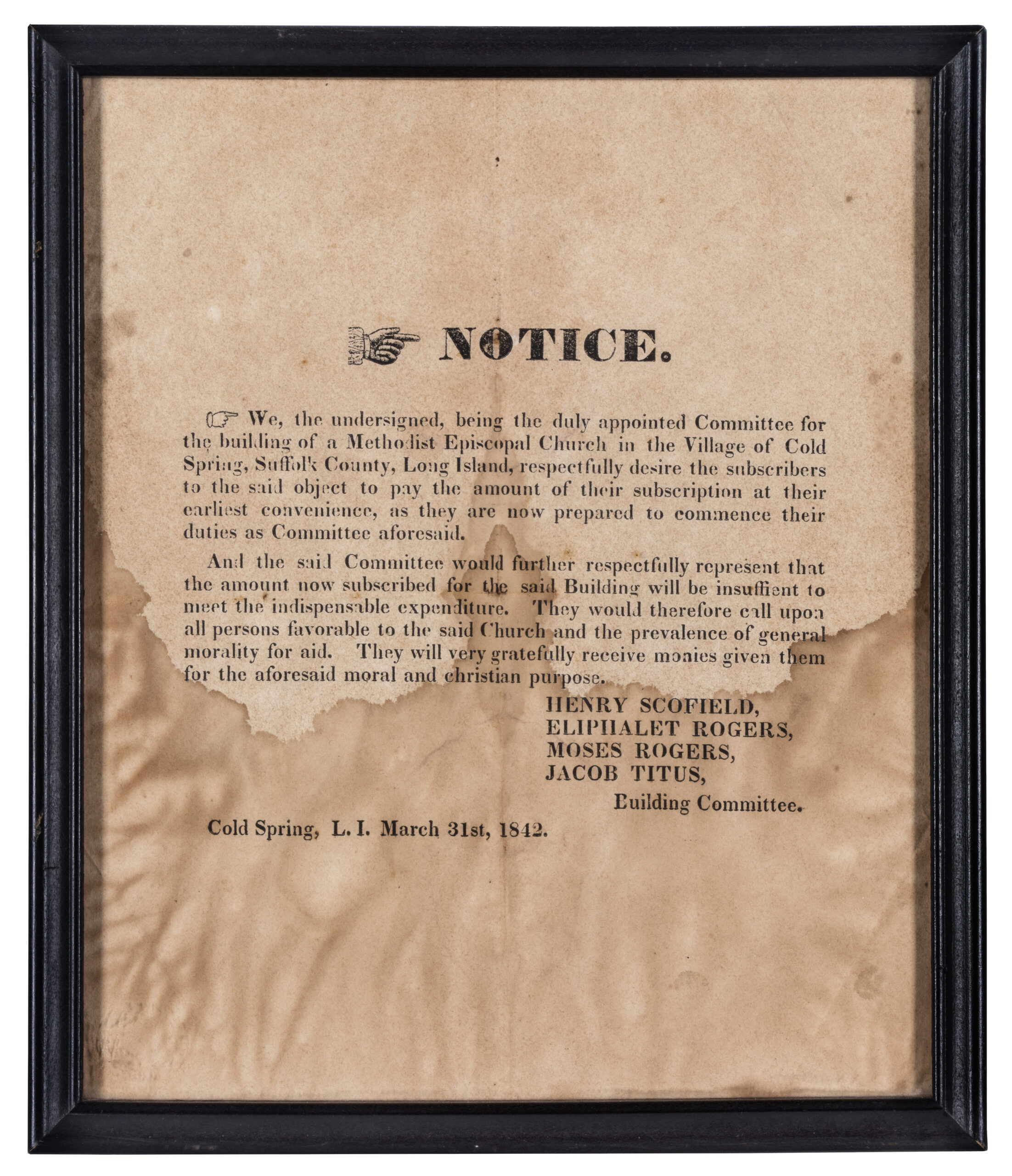

Clinton Smith Cottage, 1935–42

Ernest Cramer (1877–1953)

Watercolor on paper

Loan from the Fine Arts Collection, U.S. General Services Administration New Deal Art Project

Following the enactment of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal in 1933, German immigrant artist Ernest Cramer was hired by the Works Progress Administration to create paintings for the Federal Art Project. This watercolor by Cramer is a view down Valley Road in the historic free Black and Indigenous community of Success in present-day Manhasset. Pictured is the home of David Clinton Smith, a Black farm laborer, and Fannie J. Waters, a woman of Matinecock, Montaukett, and Shinnecock descent. Approximately 30 structures once stood in Success, which grew rapidly following the gradual end of slavery in New York in 1827, attracting freed people seeking land and homes of their own. The Lakeville A.M.E. Zion Church, constructed in 1832, is the only surviving building from Success and continues to hold services today. One of the oldest Black churches on Long Island, it was not only the spiritual center of the community, but a social one too, where families united and politics were discussed.

Bracelet and ring, ca. 1943

Nassau or Suffolk County, NY

Sheet metal

Preservation Long Island purchase, 2002.6ab

When the United States entered World War II in December of 1941, over 6 million women joined the workforce for the very first time. This bracelet and ring, which descended in the family of a female defense worker, were made from scraps of sheet metal at one of Long Island's aviation plants. The belt buckle design was often a symbol of strength and eternal memory, possibly making these pieces mourning jewelry for a fallen soldier. As men left their jobs to fight for democracy abroad, women temporarily replaced them on the factory floor. Long Island became a pivotal center for aircraft production, and thousands of women found new jobs at the region's largest aviation firms: Grumman Aircraft in Bethpage and Republic Aviation in East Farmingdale. By the end of 1943, roughly 30 percent of Grumman's 25,400 employees were women. Although the majority of this workforce was white, President Roosevelt's Executive Order 8802-signed in June of 1941-made it illegal for government contractors to racially discriminate when hiring, opening the door to African American women as well. The gains women made towards social and economic equality, however, proved to be short lived. Female workers were expected to give up their roles for returning male veterans, and the government's wartime interventions failed to unravel discriminatory policies across the country. Nevertheless, these experiences laid the groundwork for future debates over gender and racial equality.

Elias Pelletreau (1726-1810) Tankard

Elias Pelletreau (1726–1810)

Tankard, 1750-76

Southampton, New York

Silver

Preservation Long Island, gift of Howard C. Sherwood, 957.608

On the eve of the American Revolution, Southampton silversmith, Elias Pelletreau, signed the Articles of Association, an agreement adopted by the First Continental Congress in October of 1774. It formalized a boycott on British goods in response to a series of laws, or “Coercive Acts,” Parliament passed as punishment for the rebellious Boston Tea Party. Although targeted at Massachusetts, these laws were viewed as threats to the liberties of all thirteen colonies. Shortly after the signing of the Declaration of Independence, the fifty-year-old Pelletreau led a military company of senior citizens in Southampton. The patriot silversmith probably made this tankard sometime before having to flee to Connecticut following the Battle of Long Island, the first major contest of the Revolutionary War and a crushing American defeat that resulted in Long Island’s occupation by British soldiers. If you look closely, you’ll notice Pelletreau’s “EP” mark stamped on either side of the handle.

Soup Plate, 1785-95

Liverpool or Staffordshire, England

Refined earthenware (creamware)

Preservation Long Island, gift of Bertha Rose, 1977.5

The first joint session of the US Congress, established by the new Constitution, met at Federal Hall in New York City on April 6, 1789. The primary order of business was the certification of George Washington’s presidential election. Debates swiftly ensued over how to address the commander in chief of the new United States. During the Revolution, General Washington was often referred to as “His Excellency”—as seen printed on this English soup plate made for the American market. The Senate initially proposed the title “His Highness the President of the United States of America and Protector of their Liberties,” feeling it would enhance the president’s respectability abroad. In the end, Congress decided that the simplicity of “Mr. President” was more in line with the Republican values of a government “by the people.”

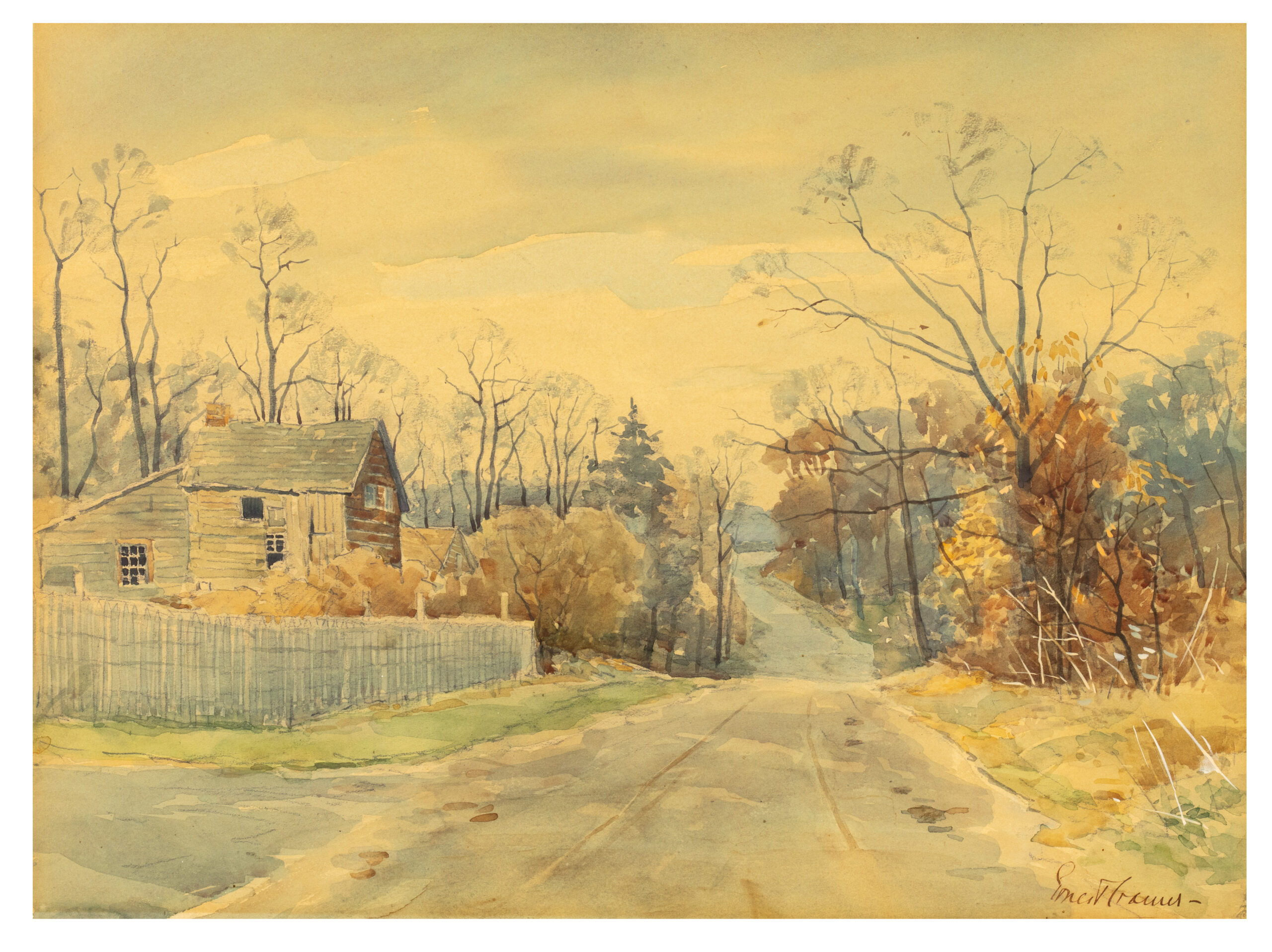

Henry Packer Dering (1763-1822), ca. 1794

Attributed to William Verstille (1757–1803)

Watercolor on ivory

Preservation Long Island purchase, 1970.31.8b

In order for the new United States government to work, it needed to raise revenue. The challenge was collecting taxes from a people who had just revolted against an imperial system of taxation. During its first session in 1789, Congress established custom houses and duties, designating Sag Harbor as one of 59 federal ports of entry. Henry Packer Dering, a well-connected merchant from a prominent local family, was appointed customs collector by President Washington. Among Dering’s duties were weighing and gauging cargoes that came into Sag Harbor, assessing and collecting duties, acting as a notary public, and hearing oaths of citizenship. Dering’s home and office, located today on the corner of Main and Garden Streets in Sag Harbor, is now owned and operated by Preservation Long Island and seasonally open for tours.

Andromache Weeping over the Ashes of Hector, ca. 1825

Attributed to Anna Charlotte Dering (1811–1905)

Litchfield, Connecticut

Silk, watercolor, ink

Preservation Long Island purchase, 2022.3.1

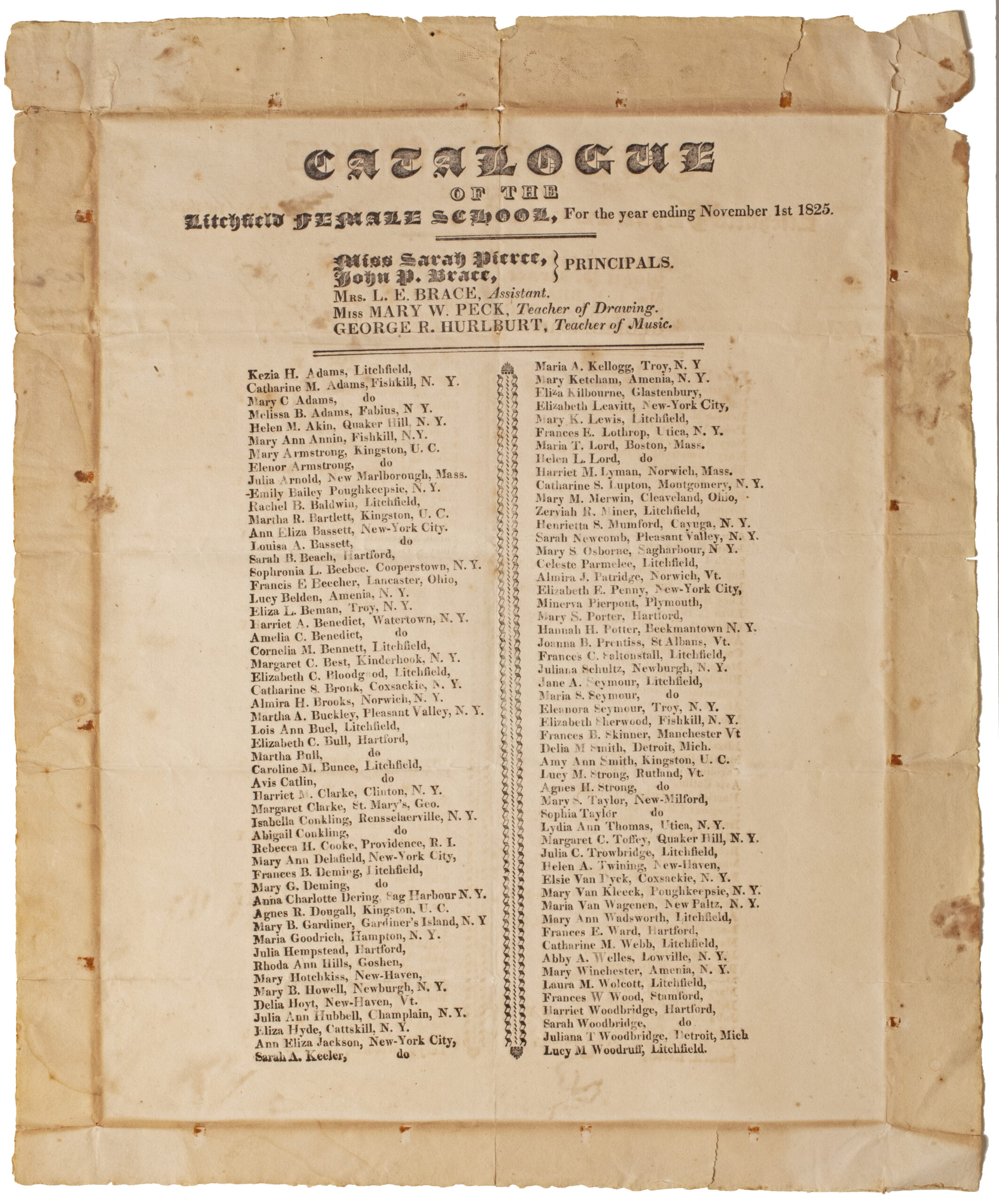

Anna Charlotte Dering was the eighth child and youngest daughter of Anna Fosdick (1769–1825) and Henry Packer Dering (1763–1822) of Sag Harbor. While in attendance at the Litchfield Female School in Connecticut, she stitched this needlework picture depicting a well-known scene from Homer’s Iliad, which she copied directly from a popular late eighteenth-century print. The Litchfield Academy was founded in 1792 and known for its advanced education. Its students learned everything from art, history, music, and geography to grammar, chemistry, and needlework. American writers and thinkers of the time advocated for the improvement of female education, arguing that since women had the earliest and greatest influence on children, daughters should be taught to uphold the democratic ideals of the young republic so that they may pass them on to future generations.

“Catalogue of the Litchfield Female School,” 1825

Paper, ink

Preservation Long Island purchase, 2022.3.2

Tea Table, 1765-85

New York City

Mahogany

Preservation Long island purchase, 2003.1

Early Americans were addicted to tea. During the eighteenth century, sipping the hot brew around a well-equipped tea table was an important social ritual that showed off one’s status and gentility. This table descended in the Floyd family and is believed to have once belonged to William Floyd (1734–1821), a wealthy landowner and the only Long Island signer of the Declaration of Independence. It is possible he purchased the table after returning from exile in 1783 to his family’s estate in Mastic, which had been occupied and plundered by the British during the Revolutionary War. Floyd opted for a table made from prized mahogany wood in a design rooted in London fashions. Following independence, influential Americans, like William Floyd, continued to style themselves after British elites. He remained a prominent political figure and served as a member of the first US Congress. One can only imagine the conversations that were held around this table during our nation’s earliest days.

Signature quilt, ca. 1862

Queens County, New York

Cotton

Preservation Long Island purchase, 2019.2

Quilts consisting of hundreds of pieces of fabric sewn together became popular in the mid-1800s thanks to the increasing availability of inexpensive printed cottons. This example descended in the Onderdonk family of Manhasset and was hand stitched in the early 1860s by members of the local Dutch Reformed Church, each of whom contributed a square signed with their name and town. Communities often created quilts such as this to commemorate major life events or to support a cause, like the US Civil War, which was then raging in the South. Women on both sides of the conflict stepped up to keep troops warm and dry, referring to their needles as weapons as they metaphorically fought alongside their “brothers in the field.” Although it is unclear if this quilt ever made it down to a soldier at camp, the ongoing fight to preserve the Union was certainly on the minds of those who painstakingly stitched it together.

An Address to the Negroes in the State of New-York, 1787

Jupiter Hammon (1711–ca. 1806)

New York City

Courtesy of East Hampton Library, Long Island Collection

Born into slavery on Lloyd Neck in 1711, Jupiter Hammon had been enslaved by three generations of the Lloyd family when he penned his An Address to the Negroes in the State of New-York in 1786, which was published for the first time the following year. Hammon was 75 years old and still in bondage. At the time, New York was home to a sizable free Black population and a growing antislavery movement. Although Hammon frames his writing around the language of Christian obedience, he refuses to accept slavery as God’s will. He hopes for freedom for his fellow Black New Yorkers, and by directly referencing the recent war for independence, lays bare the contradictions of liberty and slavery in the new nation.

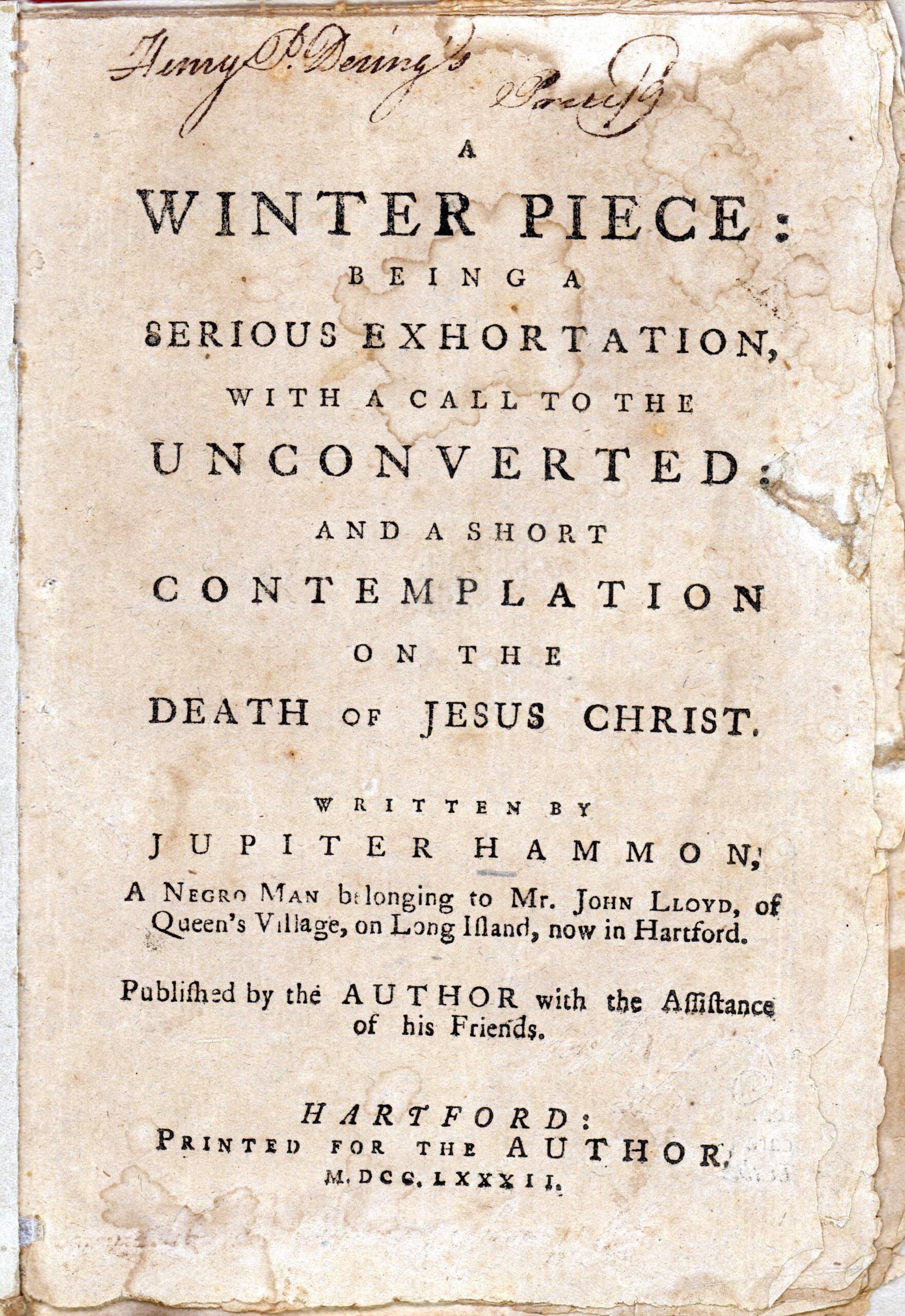

A Winter Piece, 1782

Jupiter Hammon (1711–ca. 1806)

Hartford, Connecticut

Courtesy of East Hampton Library, Long Island Collection

| Jupiter Hammon is recognized today as the first published African American poet and was one of only two enslaved authors in North America to have their works published during the eighteenth century. The other was Phillis Wheatley (1753–1784). With the power of the pen, Hammon asserted his identity despite living within a system that sought to deny him his humanity. The Revolutionary War was drawing to a close when he authored A Winter Piece while still in exile with the Lloyd family in Hartford, Connecticut. This particular copy would eventually become the possession of Henry Packer Dering, who signed his name on the title page. The evangelical sermon, however, was directed towards a Black audience which Hammon sought to convert. Across many of his writings, he argued that by adhering to moral Christian values, African Americans could rise up and assert themselves as a people within American society. |

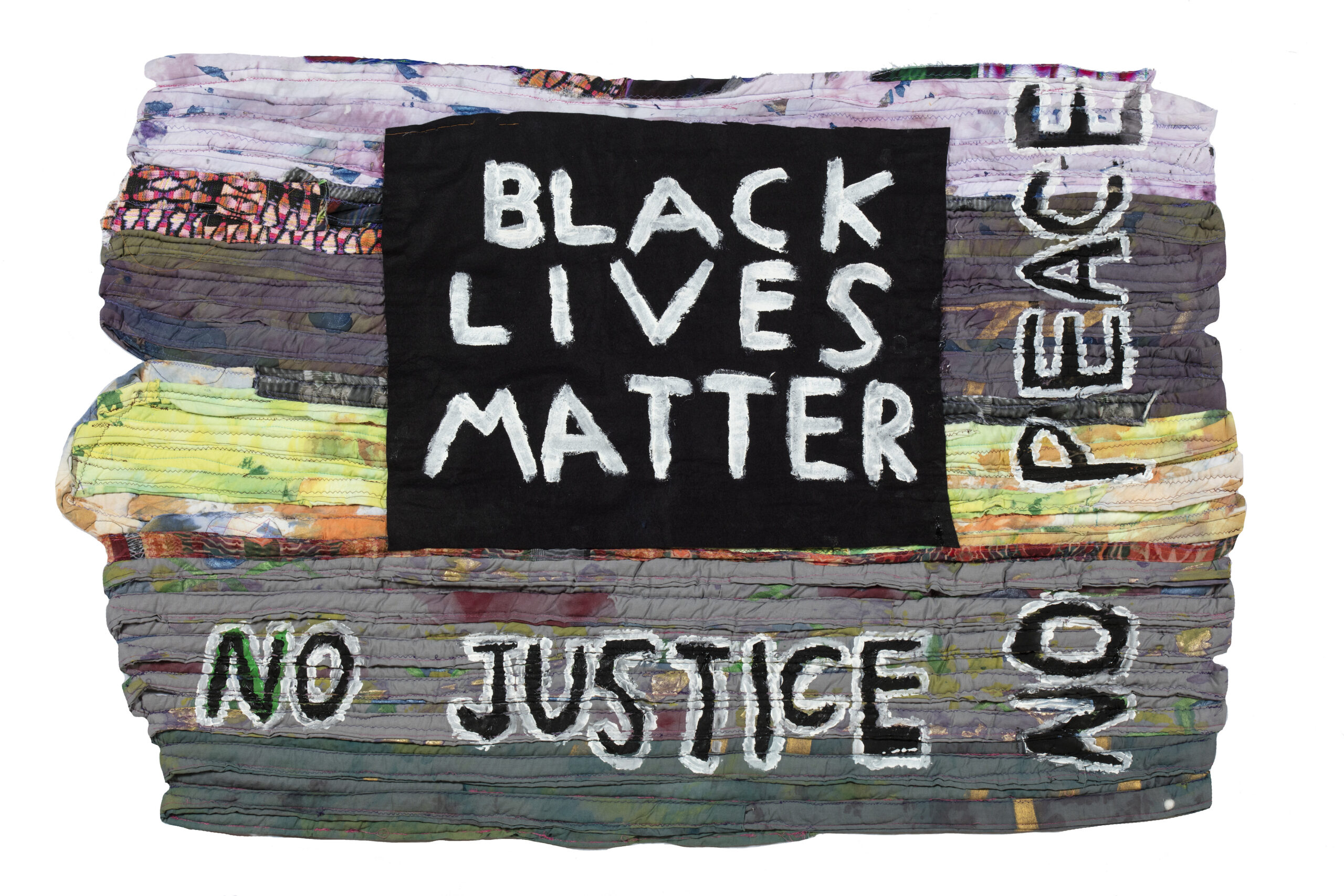

Protest Blanket, 2020

LoVid (2000–present)

Cotton, felt, synthetic fibers, dye, paint

Preservation Long Island purchase, 2020.3

In May of 2020, Preservation Long Island launched the initiative “Preserving the Present: Collecting in the Time of Covid-19” to collect art and objects that tell the diverse stories of Long Islanders living through the COVID-19 pandemic. Later that month, the murder of George Floyd sparked protests across the country against violence towards Black Americans and systemic racism. What developed was one of the most significant civil rights movements in United States history. In response, artists Tali Hinkis of LoVid and Annemarie Waugh organized A Wishful Gesture outside Gallery North in Setauket. According to the artists, the installation was a peaceful symbol that allowed people to show support for Black Americans and unity in our nation during a time of social distancing. Community members were invited to “share wishes of love, peace, and hope by placing flowers, plants, paintings, drawings, sculptures, and messages . . .” This blanket was one of the many works contributed, continuing Long Islanders’ rich history of turning artistic expressions into forms of resistance and protest—from the writings of Jupiter Hammon to other pieces left behind at A Wishful Gesture.

Shinnecock Medallion, 2021

Tohanash Tarrant (Shinnecock, Hopi, Ho-Chunk)

Glass beads, fabric, leather

Preservation Long Island purchase

The Shinnecock Indian Nation is the only federally recognized tribal community on Long Island. The region, however, is home to many other Native communities, including the New York State-recognized Unkechaugs, as well as the Montauketts, Matinecocks, and Setalcotts. Artist Tohanash Tarrant grew up on the Shinnecock Indian Reservation and comes from a long line of beadwork artists. Today, she owns Thunderbird Designs, which is based on the trading post her great grandparents opened in their front yard as a way to teach and share beadwork and culture. Beadwork is a time-consuming and meticulous art form. The gift of a beaded medallion such as this one would be bestowed upon a recipient for special occasions and worn with pride. This example incorporates the official seal of the Shinnecock Indian Nation. Designed by artist David Bunn Martine (Shinnecock, Montauk, Chiricahua Ft. Sill Apache), it depicts the history of the Shinnecock People.

Sacredness of Hills, 2018

Jeremy Dennis (Shinnecock, Hassanamisco-Nipmuc)

Inkjet print

Preservation Long Island purchase

The Sacredness of Hills is a series of photographs by Jeremy Dennis, a contemporary fine art photographer and an enrolled member of the Shinnecock Indian Nation. Dennis’s work explores Indigenous identity, culture, and assimilation and the unique experience of living on a sovereign Indian reservation. The series is based upon recurring desecrations surrounding his tribal community in Southampton. In 2018, at a residential building development on Hawthorne Road in the Shinnecock Hills, human remains were found, igniting a movement for the protection of historic Native American burial grounds. The Shinnecock Indian Nation, sister tribes, and local groups, including Preservation Long Island, came together to support local legislation that would place an immediate halt on development and prevent further disturbance of sacred burial sites. After years of rallying and protests, New York finally passed the Unmarked Burial Site Protection Act in 2023, making it a crime to remove, deface, or sell remains or funerary objects associated with Native Americans, African Americans, and Revolutionary War veterans.